Fig. 1: Hotspots of linguistic diversity

One of the most important factors affecting linguistic diversity is... time! Western Africa is close to the birthplace of human language; according to Quentin D. Atkinson, it is the birthplace of human language.

Fig. 2: Atkinson's map of language spread

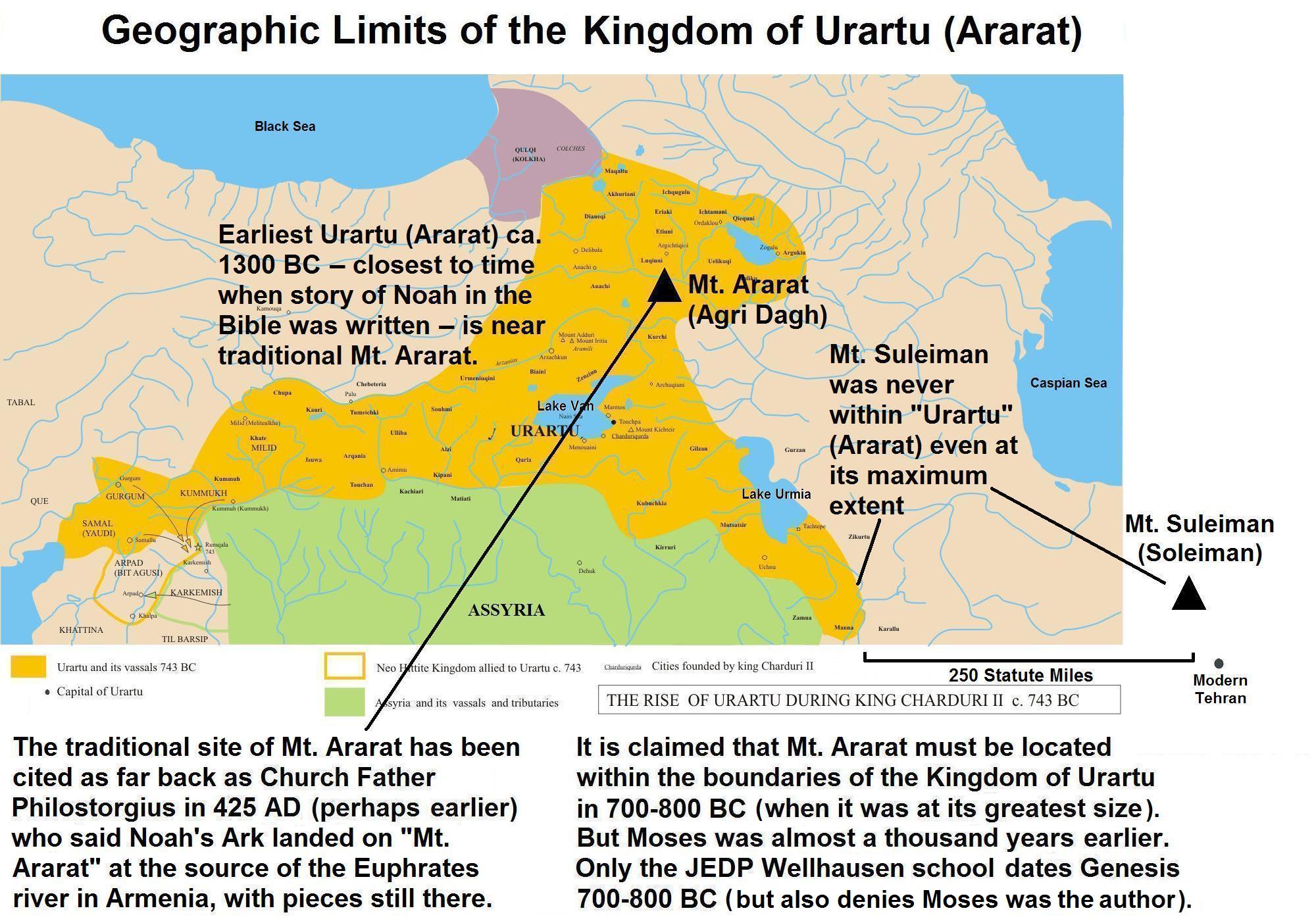

Similarly, the Caucasus is one of the oldest inhabited parts of the world; recall that according to the Biblical story of Noah, his Ark landed on Mount Ararat, in the Armenian Highlands.

Fig. 3: Armenian Highlands as the landing site of Noah's Ark

Finally, Papuans have inhabited Papua New Guinea for some 40,000 years, which allows ample time for the natural processes of language change and diversification. Consider the model proposed by William A. Foley (1986: 8-9) for the linguistic diversification of Papuan languages: if we assume the initial situation with a single community speaking a single language and a language splitting into two every 1,000 years -– both conservative assumptions, according to Foley -– "this alone would result in 1012 languages in 40,000 years", and this is not taking into account language contact, language mixing and language extinction.

A similar pattern of time translating into linguistic diversity is observable in North America as well. Let's consider the following two maps: a map of American English dialects and a map of Native North American languages.

Fig. 4: American English dialects

Fig. 5: Pre-contact distribution of North American language families north of Mexico

A quick examination of these two maps reveals the following pattern: the most diversity among American English dialects is found along the Atlantic seaboard (a more detailed map confirms this and also highlights the many local dialects of big Atlantic seaboard cities), whereas linguistic diversity among Native North American languages is at its highest along the Pacific coast. This is consistent with the time factor: speakers of English first settled in North America along the Atlantic coast, whereas Native Americans arrived via the Bering straits (then most likely a land-bridge) and migrated south before difusing eastwards.

Interesting post, Asya. I do wonder, however, about the US linguistic map, which seems rather generous with its definition of "dialect." Do northern and southern California really have different dialects? The only differences that I have noted are the use of the definite articles with highway names and numbers in the south, and the use of a few slang expression, especially "hella" and "hella sick," among young people in the north. Don't almost all western "dialects" really belong to the "lower north" category?

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comment, Martin! You are right that American English "dialects" are no match for, say, British (or Northern Italian) dialects. Neither in how geographically limited nor in how distinct they are. So the really interesting and significant differences are marked by color rather than labels on this map.

ReplyDeleteCalifornia as a whole, however, has some peculiarities of pronunciation (which do not apply to everybody, as is expected since there are so many newcomers here). These peculiarities in the pronunciation of vowels in California, known as California Shift, are studied by Penny Eckert in our department. They are also discussed here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/California_English#Phonology

Given the demography of the state, there may be more significant rural/urban divides rather than north/south divides. From the Wiki article: "In the southern Central Valley (Kern, Tulare, and Kings Counties), where a large number of people from Oklahoma emigrated during the Dust Bowl, many white Californians speak with an Oklahoma-like accent that is quite distinct from the English spoken in coastal Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay region."